Fallacies Against the Grid

I have heard many criticisms about the grid plan–It’s boring, It’s unnatural, et cetera. Having happily visited and lived within gridded towns and cities I have wondered why these perceptions exist. What is so wrong with straight streets? Following, I address some common fallacies in a defense for the grid.

Fallacy #1: The grid is boring.

This is perhaps the first reaction one might have when looking at an aerial map of a grid plan. I can almost understand why. Every block is the same size, every turn is the same 90 degrees, and every view is in the same direction (straight).

All of that being said, it is a fallacy to assume that a town’s vitality or banality is a function of the grid itself. On the contrary, these qualities are dependent directly upon zoning and economy. The grid can be as exciting or as boring as the city decides to make it. For example, the following images were clipped from grid plans using Google Maps:

How boring are those grids?

The grid generates neither excitement nor monotony though it does provide for both equally. Again, the grid is simply what your city makes of it. There are plenty of plans that look interesting from above but fail on the ground.

Fallacy #2: The grid has only been used by greedy developers trying to maximize profits.

While it is certainly true that greedy developers have preferred the grid for its efficiency and economy, the grid has been utilized over time for many more reasons than this. Its place within American history is as varied as the number of cities it has helped frame. Here are a few examples of the grid’s varied uses:

- For the greedy developer: Chicago, Illinois experienced excessive speculation in real estate during the 1800’s predominantly due to the shipping and transportation industry’s success. The grid was the perfect tool to fan the speculative flame.

- For the Quaker value of equality: William Penn founded Philadelphia on the grid plan partly because it created equal lots and blocks everywhere. Thus, his concept of brotherhood and equality was embodied in the plan itself.

- For the sale and occupation of the West: Following the purchase of the Louisiana Territory, Thomas Jefferson needed a way to sell and occupy land that at that time had never been seen before by any American. His answer—the Cartesian grid and the Land Ordinance of 1785.

- For the Plat of Zion: Joseph Smith chose the grid as the physical structure for the structured society of the new Jerusalem in the American West.

- For the Illinois Central Railroad: The railroad company established stations every 20 miles or so from Cairo to Chicago. The grid made its way to every one of these towns.

- For the right-angled house: In 1811, New York Commissioners adopted the grid because “straight sided and right-angled houses are the most cheap to build and the most convenient to live in.” The same holds true for 100-story skyscrapers, too.

- For the farming of America’s Heartland: The grid provides a framework for farming in Kansas.

Fallacy #3: The grid only belongs in urban centers.

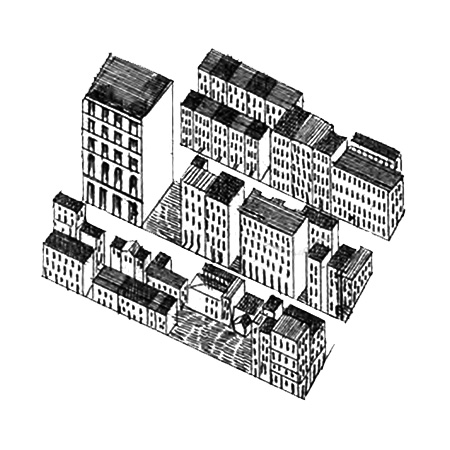

The grid is typically associated with highly developed urban centers. Because the grid was used almost exclusively as the founding framework for many of America’s towns and cities, over time these places have been built up to their urban levels as we observe them today. Given time, even a barren grid can become a modern metropolis.

Glancing at today’s urban grids, however, does not reveal the path of development that was taken. Every city in America began at one point as nothing. With that said, there are plenty of grid plans that never took off. These towns have for one reason or another resisted or lacked highly urban development opportunities. Grids can be ghost towns, farms, or suburbs. Following are images of these types of places that call the grid home:

The grids upon which these places sit in many cases have the exact same footprint as their dense urban cousins. As a case in point, Paragonah, Utah’s grid is comprised of ~400 foot blocks. And how big are the blocks in Chicago?–400 feet. Exact same grid, drastically different town.

Remember the obvious—a continuous grid of nothing but orthogonal blocks can harbor everything from farms to skyscrapers. The only thing a grid plan does is subdivide territory. No town can predict what the future will bring, but if they have a grid it is easier to accommodate that future.

Fallacy #4: The grid is harmful to the environment because it ignores topography.

This is the fallacy I admittedly am least prepared to argue, but I present it here for the sake of discussion. I cannot point to data sets or studies that prove this fallacy wrong (or right) though I am sure they exist in some form. If you have something along these lines let me know.

The grid is famous—and infamous—for ignoring topography. J.B. Jackson, who studied the American landscape and created Landscape magazine, once wrote of the grid’s “triumph of geometry over topography.” San Francisco more than any other city embodies this attribute, but where San Francisco preserved the hills, Manhattan flattened them. While in both of these cases the grid brazenly ignores the hills and valleys, it should be well noted, however, that this is just one variable in a sustainable city. While ignoring topography may do some harm it ultimately prevents others. Like everything in life, the grid has its assets and its liabilities. The following is a brief list of benefits to keep in mind. I include it here only as bullet points to expound upon later:

Benefits of the Grid:

- Walkable: With the proper block size, the grid provides an inherently walkable street network.

- Navigable: Never ask for directions again.

- Adaptable: Land uses change constantly. With blocks and lots, a new land use can simply plug-in to the existing infrastructure.

- Historical: The grid is a fundamental part of our American heritage.

- Economical: A rectangular block allows you to do the most with the least. The exact same block in Manhattan has accommodated everything from a farm to an office skyscraper. The exact same piece of dirt—now that’s economical!

- Sustainable: A rectangular block allows you to do the most with the least. The exact same block in Manhattan has accommodated everything from a farm to an office skyscraper. The exact same piece of dirt—now that’s sustainable!

- Orthogonal: We live in rectangular places / We park in rectangular spaces. The orthogonal grid—it thrives / Due to the way that we live our lives.

Conclusion

Though criticized, the grid has given us places of the most vibrant, lively, and varied characters; places of every kind and every use. All of these places, from Paragonah to Chicago, are predicated upon the exact same urban netting. If you are unhappy with where you live, blame your zoning ordinance, not the grid.