The History of Urban Form Lecture 02, PT I: Measuring Density

This is an excerpt from Otium Issue 02. To read the full issue, click here.

A Note from the Editor:

In Lecture 01, Doug divides cities between two orders: the Constitutional and Representational. These orders reflect, respectively, the public and private components of cities. In the transcription that follows here, he addresses another theme that will carry through the entire History of Urban Form series: street networks, patterns, and the measure of density.

The importance of these observations cannot be understated. Streets, as a component of the Constitutional Order, last a very long time and in many cases are as old as the cities they define. But this consideration for the longevity of streets is not fully accounted for in our modern subdivision regulations which is leading us to build cities that are unable to adapt as populations and requirements change.

Leon Battista Alberti, a 15th-century renaissance architect, provides us with the following analogy–a house is like a small city and a city is like a large house. While a house is built one wall at a time, there is a plan (a drawing or blueprint) dictating where each wall should go. Similarly, while a city is built one street at a time, there should be a plan (a drawing or survey) dictating where each street should go.

To steal one of Doug’s lines, streets are the structural framework of our cities. We should consider their placement more carefully.

Paul Knight

April 14, 2017

Measuring Density

You will recall from the first lecture Spiro Kostof’s statement about cities being a place where “a certain energized crowding” occurs. He’s talking about density. While I think his point is true–certainly midtown Manhattan is more energized and more crowded than a rural area in South Carolina–it’s insufficient simply as a definition of a city. Kostof realized this so he gave us eight more qualifiers. But density is one of the more important measures of cities, yet it is deceptively difficult to define exactly.

Normally when people talk about density they are talking about population density–the number of people per unit of land, per hectare, per acre, per square mile. Sometimes by looking at cities that way we can learn some very interesting things and make some telling observations. For example, Paris, France, has a population density of over 100 people per acre inside the peripherique. That is a lot of people. In fact it’s second only to Hong Kong as one of the most densely populated cities in the world, and actually is about double the population density of Manhattan, even though the majority of the buildings in Paris are no more than six stories tall.

Often, particularly in the city planning profession, population density is expressed as a ratio of “dwelling units per acre.” Zoning ordinances tend to deal in these terms. Whether you pick up a zoning ordinance for Dekalb County, Georgia, or for Aurora, Colorado, or wherever else in the United States, you will likely have categories of land uses and you will find how many dwelling units per acre you are allowed to build within any of those categories.

While dwelling units per acre is a simple relationship to visualize, it is actually an incomplete concept. In fact, it is one of the worst measures of density that we could possibly use because it assumes that cities are constant: that once something is built or arranged in a certain way it will be like that forever. But we know the very opposite is true. Cities change over time. They always have, and they always will.

Right now we are in this Georgia Tech lecture hall in Tech Square. But this area used to have a Chevrolet dealership and a restaurant and a parking lot and some houses. Peachtree Street began its life well over 100 years ago; all up and down it, from downtown to Buckhead, were single family residential homes. That is not the case anymore. It has all changed and has been converted to office and institutional and other kinds of uses over time. So if we look only at dwelling units per acre, or per unit of land, we are missing the bigger picture; we are not taking into account long-range planning.

Why then does it gain such popularity in the regulatory environment of city planning? The reason, it appears to me, is because it acts as a medium of exchange. A real estate developer may want twelve dwelling units per acre for their project, but the neighborhood may only want six dwelling units per acre. Through negotiations you can compromise using these numbers. While this has its benefits, in terms of measuring something over the long haul–a future that we cannot control and which may unfold in radically different ways long after we are gone–measuring density by dwelling units is deceptive. It doesn’t do us much good.

Another way of capturing similar quantities is by referencing the size of the lot. Oftentimes you will find requirements for minimum lot sizes (quarter acre, eighth acre, etc.) in zoning ordinances. Again like the number of dwelling units, this acts as a medium of exchange.

But there is another whole category of density measures that are based upon the Constitutional Order. This might be the number of intersections per unit of land, or the number of blocks per unit of land, or some other measure. Because of the relative permanence of the Constitutional Order, I think it is critically important for the long-term projection and functionality of our cities to measure density in some term pertaining to this. Specifically, we need to directly address streets and blocks and lots as they tend to outlast everything–and I mean everything–else that we build.

When Savannah, Georgia, was established in 1733-34, everything there was single family houses on tything lots. Fast forward 280 years and downtown Savannah is no longer single family. There are high rises with steel and glass and elevators, things that James Oglethorpe, the designer of Savannah’s plan, never could have imagined. Over time, everything in Savannah has changed. But you know what hasn’t change? The Constitutional Order: the lots, blocks, streets, and squares. Any measure of density of the Savannah plan (whether you measure blocks per unit area or street intersections per unit area) would be the same today as it was 280 years ago. This is important because it means that you can allow for land uses to change over time without having to rip out your infrastructure. There are ways we can learn from the cities of the past to inform how we should design the cities of the future. And I believe the key is in understanding and applying the lessons imbedded in the Constitutional Orders of cities both here in America and around the world.

However, there is a certain challenge to defining what these measures should be. We could take a square mile, or a kilometer, and simply count the number of intersections. Maryland, for example, has adopted this kind of measure. But how exactly do you measure a block? Is it the amount of acreage, or the number of hectares, in a block? Is it the total length of the roads or streets per unit of land before you get to an intersection? That, actually, is how subdivision regulations typically operate. You can go a certain number of feet (e.g., 800 feet) without having an intersection, but you cannot exceed that length without an intersection. However, these rules are violated regularly.

Block Density

And then there’s block density. All streets at some point form blocks (a block being defined as a street that closes in on itself, or an area of private property surrounded on all sides by public rights-of-way). Blocks can be relatively small. In the Fairlie-Poplar district of downtown Atlanta blocks are 200-feet by 200-feet. But blocks can also be relatively long, like some of those in Manhattan with a 900-foot length. In either of those cases, you have a different kind of block density, and certainly a different kind of block density than what you typically find in a place like Alpharetta, Georgia, in the Windward area, where the blocks take on an entirely different magnitude of size and amorphous configurations.

Blocks can be difficult to measure because they are not all rectangles. Some are trapezoids, or circles, or amoeba-shaped. Many residential areas here in Atlanta have these sort of amoeba-shaped blocks. So you have to start teasing out some of the geometric properties of these things such as block length and depth and total perimeter in order to compare them.

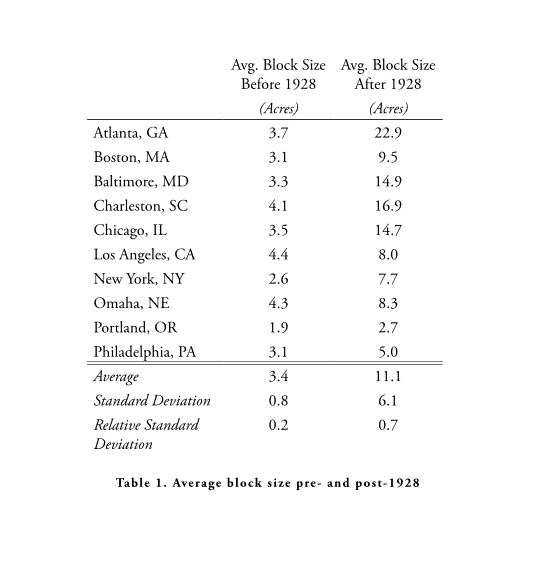

A number of years ago I became interested in this type of analysis and this question of block density. I began a little study which is only semi-scientific. I say semi- because at the moment it only includes a sample size of 200: ten cities, 20 blocks per city. I have compared the sizes of blocks built before 1928 to those built after 1928. Why 1928? Because that is the year that the Standard City Planning Enabling Statute was passed out of Congress, and that is when we have subdivision regulations being adopted in a formal way for the first time in almost every city and county, every municipal jurisdiction in the nation. It is an important watershed moment in American planning law. My analysis extends across a large geographic territory and is applicable among cities that range in age from 300 years to relatively new cities like Atlanta. Our measurements (shown in Table 1) include the number of acres in a block.

I find this fascinating. Blocks built before 1928 followed simple convention in the absence of any formal regulation. Left simply to convention, to what people agreed upon, blocks were platted and constructed in a fairly tight pattern, with a very small standard deviation of the average (only 0.8 acres, or a relative standard deviation of only 20%). After we started regulating subdivision patterns post-1928, that deviation balloons to 6.1 acres (with a relative standard deviation of 70%). This is one of history’s great ironies. Only after we started regulating block sizes did we lose consistency.

So what happened? If we move from agreement on how big a block should be prior to 1928 and we pass regulations from 1928 that directly affect block size, why does the standard deviation grow over seven times? Much of it has to do with automobiles. About three-quarters of the way through this course we will discuss the impact of the American Association of Highway Transportation Officials and the classification of streets. We will see that physics and speed and inertia play a leading role in defining the forms of our cities. Rather than considering how to maximize a unit of land for flexibility over time, we have transitioned our priorities over to short-term traffic flow. This truncates our vision and limits our potential. Instead of developing hundred-year plans (as was done in places like Washington, D.C., and the island of Manhattan) we now focus on the minutia. We design our cities from the inside out. We focus on the distance between intersections to signal for a design speed of let’s say 40 miles per hour, which is 1,800 feet. So if you have a parcel that is adjacent to a Level One service you can only signal at 1,800 feet. That means that there is no intervening intersection. If you square 1,800 feet that’s 74.4 acres — that’s a big block. There is a peculiar, almost chemical reaction between the standards that are set by the transportation officials and the subdivision patterns that materialize as a result.

We will explore these enormous implications later on in the course, but as a quick comparison, we can look at Paris, Brasilia, Atlanta, and Istanbul, all at the same scale, and we can see their individual street patterns and densities of blocks and intersections.

Types of Street Systems

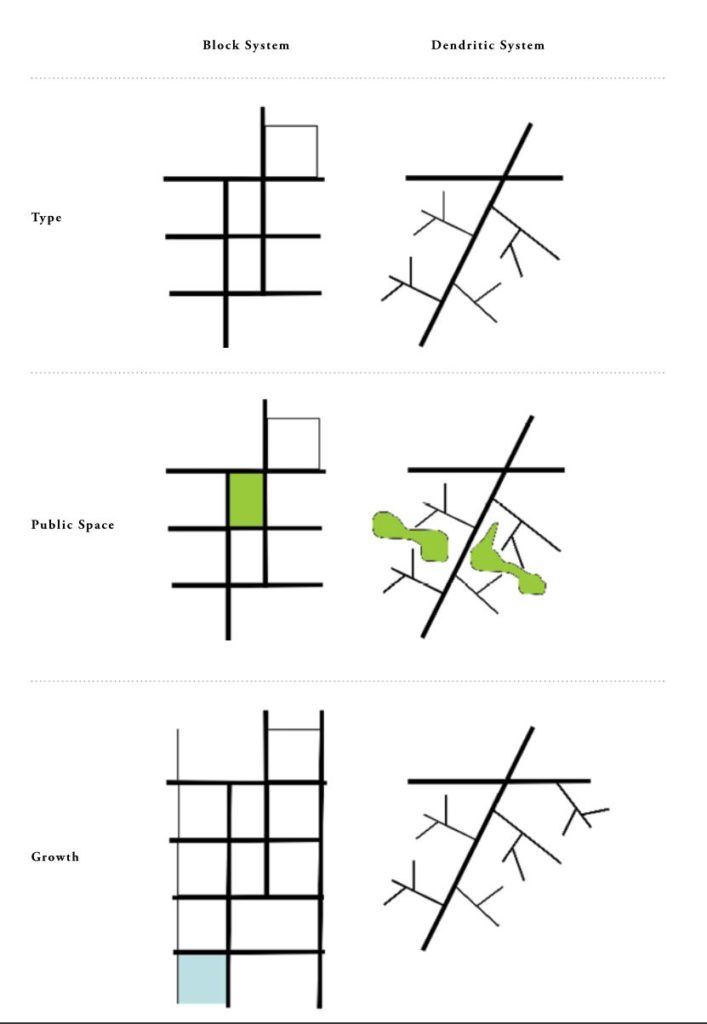

As I have said, streets are the primary structural unit of the city. And as far as I know there are only two broad types of street systems: dendritic and block.

The Dendritic System resembles the pattern of tree roots, dendrology being the study of trees. This is a very old pattern. The pattern also resembles streams, the way small streams become bigger streams and eventually you get to a fourth order stream like the Chattahoochee River. This “tributary” analogy may be more appropriate within our contemporary context of vehicular flow, but for now we will use the dendritic analogy.

The other system is the Block System. Even in dendritic systems, at some point a block will form. The difference is that there is no internal street other than perhaps an alley or a driveway or something else which is actually a public right of way in the interior of the block.

There are advantages and disadvantage to these systems and different ways of analyzing them. One way is in terms of the visibility of public space. In a dendritic system the public space is often behind individual parcels. We can see this in the Windward area of Atlanta and we will also see this in Sana’a, a medieval city in Yemen. Public space is on the private side of the parcel, the interstitial space typically not visible from the public right-of-way. However, in a block system public space is visible from the public right-of-way. So if the public space is to become the repository of a public building, or of a memory, or a monument, or something important then there is a certain advantage that blocks have over dendritic structures.

Blocks are also easier to add on to. There is a somewhat logical structure and different opportunities for connections. However, it is very difficult to figure out how to add onto a dendritic system. Connections are messy and oftentimes are made on the margins. What results is a pattern of infrastructure that is not conducive to changes in land use over time. The example I gave earlier of this block we are standing on right now here in Tech Square: without changing the streets you can have tremendous change as I have witnessed over the last fifty years in the use of these individual blocks. From a restaurant to a parking deck. From a car dealership to a bank owned by Georgia Tech. And this building we are in, the Scheller College of Business, sits on land which used to have single family houses and a stereo repair shop.

What Do Cities Have In Common

You can find the block and dendritic systems in cites throughout time and around the world. In Baghdad, for example, we can look at an early 20th century subdivision and find rectangular blocks, main streets, secondary streets, and tertiary streets. We can compare that to the historic core dating back to the 15th century of the common era where we find a dendritic structure.

Likewise, we can look at downtown Atlanta which dates to about 1853. What we see is a series of rectangular blocks and some rotated blocks, the explanation for which we will come to at the end of this course, but then here in Midtown what we see is a residential planned garden suburb from the turn of the century, which also is a block structure but the blocks are not rectangular.

Again, it’s the block structure and the distance to intersection that becomes the critical device.

We can also compare the relative scales of these patterns. While the historic core of Baghdad and late-20th century suburban Atlanta share the same dendritic street patterns, their scales are dramatically different.

These different structures of the Constitutional Order are not purely a function of culture; they are, in fact, correlative more to time and when they were built. For example, two ancient cities (Assur and Damascus) are both quite old but have very different street structures. Assur is a dendritic structure while Damascus originally was a gridded structure with orthogonal blocks. From an urban form perspective these cities share relatively little in common. Now take Philadelphia, a city laid out by surveyor Thomas Holmes for the founder William Penn in the last quarter of the 17th century. The elements of Philadelphia exhibit a structure that is more similar to Damascus than Damascus is to Assur. And the Windward subdivision here in Atlanta is more similar to Assur than it is to Philadelphia.

These are significant observations because it places cities side-by-side within the context of urban form even though they may be separated in time by thousands of years. History is a valuable design tool especially in the context of urban form because its lessons never expire.