Walking in Brooklyn

I lived in Atlanta, Georgia, for almost 20 years, but earlier this year I moved to Brooklyn, New York. I had always wanted to live in New York, especially after I began studying urban design and city planning. New York is an urban Petri dish that evolved quickly, making it a great laboratory for studying urban form, building codes, policy, etc. Urban design is one of those professions that benefits greatly from on-site experiences, so my girlfriend and I took up residency in said laboratory.

Location

We decided to move to Cobble Hill, a neighborhood in Brooklyn (one of New York City’s five boroughs1). While the area was occupied by the Dutch shortly after their purchase of Manhattan from the Native Americans in the 1600s (or so the story goes2), Cobble Hill was largely developed in the mid-to-late-1800s along with the rest of the city.

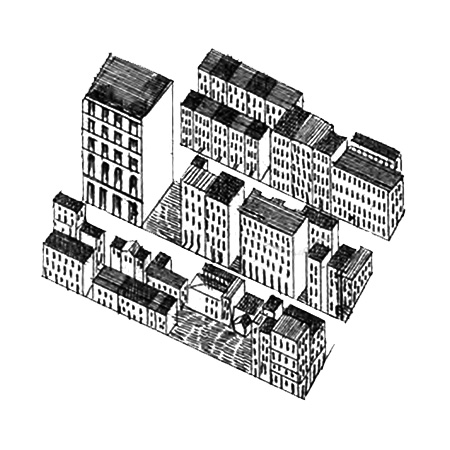

The development pattern follows the established formula of the period: rectangular blocks (in our case approximately 200 feet by 500 feet), main commercial streets lined with small storefronts (approx. 20 feet wide), and residential streets with three-story brownstones of similar fenestration but differing materials. The result makes for a beautiful consistency (like that found in London or Paris) and, more importantly, the most walkable urbanism I have ever experienced.

I have now lived here for six months. Here are some of my experiences on Brooklyn’s walkability.

Convenience

The level of convenience here cannot be overstated. Need an extension cord? There’s one available a block away. Thai food? Across the street. Pet daycare? Three blocks down. Root canal? Next to the Thai food. Coming from Atlanta, where a majority of life’s daily destinations are a car ride away, it is a powerful, liberating feeling to have everything quite literally right outside my door.

This allows me to do my errands ad hoc, here and there. If I’m walking my dog, I’ll drop off a package at UPS along the way. If I’m grabbing a coffee, I’ll also pick up some trash bags. If I’m just wandering around, I might come across a Dungeons & Dragons meeting house and…well, never mind. Brooklyn promotes “decentralized living.” There’s simply not enough consolidated space for any one spot to have everything (there are no big-box stores or strip malls on giant parking lots); the goods and experiences of life are distributed among a greater number of smaller spaces.

Much of my life here takes place within a three-block radius (right at 660 feet, or 1/8th mile, sometimes referred to as a “furlong” among us urban historians). Within that radius, there are 96 individual shops. For comparison, in Atlanta I lived in Inman Park near Krog Street, one of the more walkable spots in the city. However, the closest business (a restaurant) was still 900 feet away.

Exchange

Back here in Brooklyn, things also seem more personal. When I drop off some film to get developed and the man behind the counter looks at me and says “thank you so much,” it just feels good to make a direct exchange with someone who is doing the actual work. It is a microcosm of a free market – I give you this money to do that service. Contrary, at a big-box store (offline or online) that exchange becomes lost in the machinery of automation, logistics, and stratified power hierarchies.

In Atlanta, much of my everyday experiences were segregated from one another: live here, drive to work there, drive to shop over there, walk the dog around the block and call it a day. The Brooklyn experience is magnitudes more complex; so complex, in fact, that emergent properties often appear.3 A simple transaction can lead to a new relationship (friendly or otherwise), new information (“Did you hear about the construction on Bergen Street?”), or just spark a little random joy in passersby (“Mommy, look at that big white dog!”).

Neighbors

The kind of convenience and “life density” here in Brooklyn is made possible by the sheer number of people that live here. It’s not an overwhelming population density, though. It’s just enough people to feel lively and safe, but not so much to make you feel smothered.4 In Brooklyn overall, there are 59 people per acre; this is half the density of Manhattan (111 people per acre), but over 10 times that of Atlanta (with only 5.8 people per acre). This is an important data point to link to my observations.

Population density is like gravity in physics: it is one of the “fundamental forces” that shapes cities. As social animals, each person has a certain amount of “gravity:” the more people, the higher the attractive force for other people. Think back to the times you’ve seen a small gathering or someone looking in a certain direction: your social-animal brain compelled you to wonder “What are they doing? What are they looking at?” You were drawn closer. This “gravity” also comes from personal networks (one person moving to a city may result in their extended family moving there as well) or skills (a la Silicon Valley). People beget people.

That said, too much population density risks an implosion of unsanitary crowding (like that seen in the tenement housing projects of 1800s industrial New York5). Too little, however, leaves little attractive force which risks a continuous expansion further out and away from the city center itself (like we see in Atlanta and its expansive suburbs). I’m not sure how to control for this (or if it can be controlled at all) but at this moment in time Brooklyn seems to hit the sweet spot.

Conclusion

There is much more for me to learn here, but I hope you found my current perspective valuable. Come visit Brooklyn, experience it for yourself, and we can compare notes over coffee (there are eight coffee shops within a furlong from me).

CITATIONS:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boroughs_of_New_York_City

- http://cobblehill.nyc/knowledge_base/cobble_hill_history/

- Emergent properties stem from complex systems and show different characteristics that would otherwise emerge from each individual unit of that system. Ant colonies are a good example: no individual ant “manages” the entire colony, but collectively they act as a single organism that manages itself. Edward Glaeser brilliantly explores this concept in his book Triumph of the City, which I highly recommend.

- For reference, when I go into Manhattan I feel smothered.

- https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/jacob-riis/riis-and-reform.html